Abstract

Purpose This national study was designed to audit anatomical outcome and complications relating to primary surgery for rhegmatogenous retinal detachments. This paper presents success and complication rates, and examines variations in outcome.

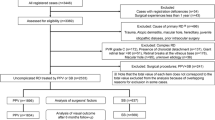

Methods Sampling and recruitment details of this nationwide cross-sectional survey of 768 patients of 167 consultant ophthalmologists having their first operation for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment have been described. The main clinical outcomes detailed here are anatomical reattachment at 3 months after surgery and complications related to surgery. Consultants with a declared special interest in retinal surgery and able to perform pars plana vitrectomy were designated specialists for the analyses.

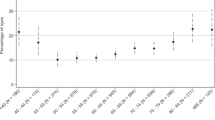

Results Overall reattachment rate with a single procedure was 77% (95% CI 73.9–80.2). There were significant differences in reattachment rates between specialists and non-specialists. Without allowing for case-mix, specialists had a reattachment rate of 82% (95% CI 77.9–85.7) with a single procedure and non-specialists 71% (95% CI 65.9–76.0). Allowing for case-mix, there was a significant difference between specialists and non-specialists for grade 2 detachments of 87% and 70% respectively (P < 0.0001). Analysing detachments by break type, the largest difference between specialists and non-specialists was observed for retinal detachments secondary to horseshoe tears, 80% and 68% respectively (P < 0.003). Specialists met the standards set for primary reattachment rates, while non-specialists did not. Over a third of patients had at least one complication reported at some point during the audit period.

Conclusions Significant differences were seen in reattachment rates between specialists and non-specialists, overall and for specific subgroups of patients. This study provides relevant, robust and valid standards to enable all surgeons to audit their own surgical outcomes for primary retinal detachment repair in rhegmatogenous retinal detachments, identify common categories of failure and aim to improve results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prior to Gonin’s understanding of the pathophysiology of retinal detachment, surgical or spontaneous cure was rare.1,2 He laid the foundations for successful retinal detachment surgery in the 1920s in a largely unselected series3 and the proportion of patients judged suitable for surgery and the proportion of patients with successful anatomical outcome rose over the following decades.4,5,6

Variation exists in the reattachment rates of published series for reasons which remain unclear.7,8,9,10,11 With such variation existing in the literature and no consensus on how to explain the differences, setting robust, valid and relevant standards for local audit becomes difficult.

This national study has focused on primary surgery for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment and the design allowed the success rates for detachments of differing morphology to be examined in detail.

Methods

The methodology and validation studies have been described in detail in our previous paper12 but in summary, clinical data were collected in a national cross-sectional survey of all consultants who performed retinal detachment surgery in the National Health Service. Consultants selected patients undergoing primary surgery for simple rhegmatogenous retinal detachments according to study eligibility criteria and supplied data on patients’ pre-operative factors, type of surgery, anatomical outcome and complications.

The main outcome measure was complete retinal reattachment at 3 months post-operatively. Secondary outcome measures were complication rates. These were compared to pre-determined audit standards set by the steering committee.12 Detachments were graded into four categories for subgroup analysis.12

Results

Reattachment

Anatomical outcome at 3 months was known in 95.3% (732/768) of the eligible patients. Table 1 outlines the management of all patients by specialists and non-specialists respectively. The reattachment rates at 3 months are given in Table 2. Bearing in mind reported activity rates,12 the estimated annual success rate for primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachments in the United Kingdom (UK) is 81.0% for all patients after a single procedure. This equates to 8339 of the 10 284 primary procedures for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment being successful.

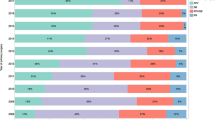

Success rates by specialist interest

The rates of reattachment by specialist interest are shown in Table 3. Specialists have significantly higher reattachment rates at 3 months than non-specialists for both a single procedure to reattachment and when multiple procedures by the same surgeon have been carried out. These results have not been adjusted for case-mix. Non-specialists fail to meet the standards set for the audit12 for anatomical reattachment for both a single and multiple procedures.

A number of patients were lost to follow-up at 3 months but whether their retina had reattached or not following surgery was known at 1 month. The reattachment rate for specialists at one month has increased slightly compared to 3 months, to 82.5% (340/412), as a number of patients with successful surgery who were discharged early have been included. The reattachment rate for non-specialists at one month has decreased slightly compared to 3 months, to 70.2% (236/334).

Success rates by grade of surgeon

When the proportion of patients who had a successful anatomical reattachment with a single procedure was examined by grade of surgeon, specialist consultants had the highest success rates. For most detachments in the study, the primary surgeon was a consultant. A non-consultant was the primary surgeon for relatively few detachments and with the exception of fellows their results fall below the standards for the audit,12 whether supervised by a consultant or not. Reattachment rates for each grade of surgeon are given in Table 4. The reattachment rates when non-consultants were the primary surgeons are given by grade of assistant in Table 5.

Success rates by grade of detachment

Reattachment rates by grade of procedure and type of operative procedure used are given in Table 6. Grade 1 detachments, a single tear with less than 1 quadrant of associated retinal detachment, had the best rates of reattachment, though over 11% of those operated on by specialists, and 15% of those operated on by non-specialists failed to be reattached with a single procedure. Specialists used conventional drainage surgery in a higher proportion of grade 1 detachments than non-specialists, though reattachment rates were similar. Nine patients had a pars plana vitrectomy for a grade 1 detachment.

The most significant difference in reattachment rates between specialists and non-specialists was seen with grade 2 detachments (single or multiple breaks within the same quadrant and/or less than two quadrants of retinal detachment), 87% and 70% respectively. This was also the largest group of detachments in the study. The reattachment rate for specialists differs little from their rate for grade 1, but the failure rate for a single procedure was double for non-specialists, due to a preponderance of early failures.

The reattachment rates for the more complex grade 3 detachments were lower compared to grades 1 and 2, by specialists and more so by non-specialists. Non-specialists performed fewer grade 3 detachments than specialists and the disparity in activity between the two groups of surgeons increases for grade 4. Morphologically, grade 4 was a heterogeneous group of detachments and it would be difficult to comment on the success rates for either group of surgeons.

Success rates by break type

Table 7 gives reattachment rates for detachments stratified according to the nature of the retinal break. The reattachment rates for horseshoe tears are marginally lower than the overall rates and there is a significant difference between specialists and non-specialists. Reattachment rates for both groups of surgeons are slightly higher for a single procedure for retinal holes than their overall rates and while a statistically significant difference remains between the two groups, it is less marked. The numbers of detachments in the mixed tear and hole group is smaller than the first two groups. The difference in reattachment rates between the two groups is not statistically significant. Though the numbers in the dialysis group are small, they have better reattachment rates than other types of breaks with similar rates for both groups of surgeons. There were few detachments secondary to giant retinal tears and specialists performed all surgery. The reattachment rate is well below the overall rate.

Multivariate analysis

The results of multivariate analysis show that specialist status was the most important indicator of successful anatomical reattachment with a single procedure.

Allowing for the other factors, patients operated on by specialists were over three times more likely to have successful anatomical reattachment with a single procedure (odds ratio 3.6, 95% CI 2.2–5.9). Increasing grade was associated with decreased likelihood of successful anatomical reattachment. Grade 2 detachments were nearly three times less likely to reattach with a single procedure compared to grade 1 (odds ratio 0.36, 95% CI 0.16–0.84). Grade 3 and grade 4 were even less likely to reattach compared to grade 1 having odds ratio 0.17 (95% CI 0.07–0.41) and 0.15 (95% CI 0.05–0.40) respectively.

The delay between presentation and surgery ranged from 0 to 552 days (median 2 days). Patients with a delay between presentation and surgery of over 30 days, were slightly more likely to have a successful anatomical result compared to patients whose operation was performed within 1 day of presentation (odds ratio 4.5 95% CI 1.1–18.6). This supports the notion that patients who were selected to wait for surgery were those who had a good prognosis for reattachment and that delaying their surgery did not change this. Type of surgery, break type and high-risk status were not associated with a poorer outcome in the multivariate analysis.

Complications

Over one third of patients had at least one complication noted at some point in the 3-month follow-up period. Overall complication rates for each time point are shown in Table 8. There was no significant difference between the overall complications rate of specialists and non-specialists.

Per-operative complications

The rate for reported unplanned sub-retinal fluid drainage was 2.7% (21/768) and that for retinal incarceration 0.7% (5/768). The sample met the audit standards12 for retinal incarceration and unplanned sub-retinal fluid drainage and there was no significant difference between specialists and non-specialists. Other complications reported included corneal abrasion (five patients), scleral rupture (two patients), elevated intra-ocular pressure requiring intervention (eight patients), and iatrogenic break (six patients). Iatrogenic breaks occurred only in patients undergoing pars plana vitrectomy, which gives a rate of 4.9% (6/122) for iatrogenic break for patients having pars plana vitrectomy in this cohort. Information was specifically sought on intra-ocular haemorrhage. In total, 7.2% (55/759) patients were reported to have had an intra-ocular haemorrhage, but details of the site, extent and significance were not generally reported.

Early complications

Only one patient developed endophthalmitis post-operatively (0.1%). The sample met the audit standards12 for endophthalmitis. Other reported complications in the early post-operative period included diplopia (six patients), elevated intra-ocular pressure (13 patients), choroidal effusion (four patients), cataract (four patients), plomb problems (four patients) and vitreous haemorrhage (four patients).

Late complications

The reported rate for macular pucker was 4.4% (34/768), proliferative vitreoretinopathy was 4.8% (37/768) and late diplopia was 2.6% (20/768). The sample met the audit standards12 for these complications and there was no statistically significant difference in rates between specialists and non-specialists. A significantly higher proportion of non-specialists’ cases had explant related complications than specialists’ cases (14/343, 5/425 respectively, P < 0.04) during the 3-month follow-up. Other recorded complications in the late post-operative period were cataract (12 patients), cystoid macular oedema (three patients), uveitis (three patients), anterior segment ischaemia (one patient), and rubeosis (one patient).

Discussion

Overall the sample met the audit standards12 for reattachment but this combined outcome measure conceals a difference in reattachment rates between specialists and non-specialists. Most non-specialists performed few detachments annually and their lower success rate may be related to this or poor case selection. Other than for the simplest detachments (grade 1—a single retinal break with less than one quadrant of associated retinal detachment) and dialyses, non-specialists perform below the reattachment rates achieved by specialists. Non-specialists have the option of choosing which detachments to operate on and which to refer, so that reattachment rates should be demonstrably comparable to or better than those of specialists if surgery by non-specialists is to be justified and sustainable in terms of clinical governance. The results for grade 1 surgery were above the set standard,12 although many specialists would be disappointed at a failure rate of over 11% for grade 1 detachments.

Grade 2 detachments (single or multiple breaks within the same quadrant and/or less than two quadrants of retinal detachment) formed the largest group of detachments within the survey. The statistically significant differences in reattachment rates between specialists and non-specialists persists even in the cohort limited to conventional surgery implying that surgical technique in addition to case selection is significant.

Early failures generally result from incomplete closure of breaks at primary surgery or missed primary breaks.13,14 The fact that missed breaks are significant implies that successful management of retinal detachment requires good surgical skills, careful case selection and meticulous examination of the patient prior to surgery, in order that all retinal breaks and other relevant retinal pathology be identified and managed appropriately.15 The low rates of surgery performed by non-specialists, possibly reflecting in part low numbers of patients presenting to them with retinal detachments, may not be sufficient to maintain such clinical and surgical skills thereby contributing to higher failure rates.

Non-consultants were the primary surgeons in relatively few detachment repairs. With the exception of fellows, their reattachment rates fell well below the standard set for the audit. Specialist registrars when assisted by a non-specialist consultant had far lower reattachment rates than those assisted by specialist consultants, which suggests that the training offered in such circumstances, may be inadequate. The complication rates for trainees were similar to those of consultants, indicating that primary failures were not secondary to complications but poorly performed surgery. Careful patient selection has been shown to provide acceptable reattachment results for trainees.9 In the context of clinical governance, training must be shown not to compromise patient safety.

The retrospective design of the study could lead to under-reporting of complications. Despite this, over one third of patients were reported to have had at least one complication reported during the 3-month follow-up period. The standards set for complications were met, and in some circumstances the reported rates were better than the audit requirements. The only complication with different rates between specialists and non-specialists was protruding explants. The previous comments about the maintenance of surgical skills may similarly apply in this instance.

Until recently all surgeons in the UK were required to perform retinal detachment surgery before the award of a certificate of higher surgical training. Recent changes to training programmes have removed the requirement for trainees to perform any practical retinal surgery. Unless trainee surgeons have undertaken specialist training in retinal surgery, they cannot be expected to have sufficient expertise in the surgical management of retinal detachments on becoming a consultant.

To date there has been no co-ordinated planning for the provision of surgical retinal services in the UK and the current service has developed in an ad hoc fashion with wide regional variations in the numbers of specialist retinal surgeons. Historically there has been a drift towards retinal surgery being performed increasingly by retinal sub-specialists. The results of this audit confirm that retinal sub-specialists do on average achieve better surgical outcomes compared with non-specialists. If primary retinal detachment surgery were to be performed exclusively by sub-specialists there would be a need to expand specialist centres in each region. Such a change in practice would have significant resource implications and would impact not only on provision of patient care but also on surgical training. The authors do not consider it their role to formulate recommendations regarding service provision based on the results of this audit and this study neither endorses nor refutes the practice of any individual surgeon. These results do however support the notion that surgeons with a declared interest, specialist post-graduate training, and a greater throughput of retinal detachment cases achieve better surgical outcomes.

This national audit provides an indication of success rates for a variety of groups of surgeons and suggests possible areas of concern, where performance may not be as good as expected. It is hoped that these results, and the standards set by the steering committee, will be useful as benchmarks against which all surgeons can judge themselves when auditing their own surgical practice to improve further on primary success rates. Outcome information in relation to case mix may assist non-specialist surgeons in deciding which patients to operate on and which to refer on to a retinal specialist.

References

Gonin J . La traitement local du décollement rétinien. Revue General Ophthalmologie 1929; 43: 381–386

Gonin J . Guérisons opératoires de décollements rétiniens. Revue General d’Ophthalmologie 1923; 37: 337–340

Gonin J . Le Décollement de la Rétine. Pathogénie – Traitment Librarie Payot et Cie: Lausanne 1934

Rosengren B . Results of treatment of detachment of the retina with diathermy and injection of air into the vitreous. Acta Ophthalmologica 1938; 16: 573–579

Smith TR, Pierce LH . Idiopathic detachment of the retina. Arch Ophthalmol 1953; 49: 36–44

Dufour R, Erpelding G . Resultat du traitement en fonction de la situation clinique. Mod Probl Ophthal 1965; 3: 229–248

Sullivan PM, Luff AJ, Aylward GW . Results of primary reattachment surgery: A prospective audit. Eye 1997; 11: 869–871

Laidlaw DAH, Clark B, Grey RHB, Markham RHC . (letter). Eye 1998; 12: 751

Comer MB, Newman DK, George ND, Martin KR, Tom BDR, Moore AT . Who should manage primary retinal detachments?. Eye 2000; 14: 572–578

Minihan M, Tanner V, Williamson TH . Primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: 20 years of change. Br J Ophthalmol 2001; 85: 546–548

Ah-Fat FG, Sharma MC, Majid MA, McGalliard JN, Wong D . Trends in vitreoretinal surgery at a tertiary referral centre: 1987 to 1996. Br J Ophthalmol 1999; 83: 396–398

Thompson JA, Snead MP, Billington BM, Barrie T, Thompson JR, Sparrow JM . National audit of the outcome of primary surgery for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. I. Sample and methods. Eye 2002; 16: 766–770

Chignell AH, Fison LG, Davies EWG, Hartley RE, Gundry MF . Failure in retinal detachment surgery. Br J Ophthalmol 1973; 57: 525–530

Wilkinson CP, Bradford RH . Complications of draining subretinal fluid. Retina 1984; 4: 1–4

Tasman W . History of retina 1896–1996. Ophthalmology 1996; 103: S143–S152

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the consultants who participated in both phases of the audit without whose support the study would not have been possible. They would also like to thank Mr AH Chignell and Mr B Foot for participating in the steering committee; Mr AT Moore as past chairman of the audit committee; Miss M Hallendorff and the staff of the Royal College of Ophthalmologists and Mr CR Canning and Mr A Chopdar for piloting the clinical questionnaires.

This study was supported by core audit funding from the Department of Health. Presented in part at the Royal College of Ophthalmologists Annual Congress 1999 and 2000 and the Oxford Ophthalmological Congress 2000. Financial/proprietary interest: None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thompson, J., Snead, M., Billington, B. et al. National audit of the outcome of primary surgery for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. II. Clinical outcomes. Eye 16, 771–777 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700325

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700325

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Stratifying the risk of re-detachment: variables associated with outcome of vitrectomy for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in a large UK cohort study

Eye (2023)

-

Weight-adjusted caffeine and β-blocker use in novice versus senior retina surgeons: a self-controlled study of simulated performance

Eye (2023)

-

Artificial intelligence using deep learning to predict the anatomical outcome of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment surgery: a pilot study

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2023)

-

Assessment of epiretinal membrane formation using en face optical coherence tomography after rhegmatogenous retinal detachment repair

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2021)

-

Factors affecting visual recovery after successful repair of macula-off retinal detachments: findings from a large prospective UK cohort study

Eye (2021)