Abstract

Purpose

To examine the basic surgical training received by Senior House Officers (SHOs) in ophthalmology and the influence on training of sociodemographic and organisational factors.

Methods

Cross-sectional survey of SHOs in recognised UK surgical training posts asking about laboratory training and facilities, surgical experience, demographic details, with the opportunity to add comments.

Results

A total of 314/466 (67%) questionnaires were returned. In all, 67% had attended a basic surgical course, 40% had access to wet labs and 39% had spent time in a wet lab in the previous 6 months. The mean number of part phakoemulsification (phako) procedures performed per week was 0.79; the mean number of full phakos performed per week was 0.74. The number of part phakos performed was negatively correlated, and the number of full phakos completed was positively correlated, with length of time as an SHO. Respondents who had larger operating lists performed more full phakos per week (P<0.001). Compared to men, women were less likely to have access to a wet lab (P=0.013), had completed fewer full phakos per week (P=0.003), and were less likely to have completed 50 full phakos (P=0003). SHOs’ comments revealed concerns about their limited ‘hands on’ experience.

Conclusions

There are significant shortcomings in the basic surgical training SHOs receive, particularly in relation to wet lab experience and opportunities to perform full intraocular procedures. SHOs themselves perceive their training as inadequate. Women are disadvantaged in both laboratory and patient-based training, but minority ethnic groups and those who qualified overseas are not.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Postgraduate medical training in the United Kingdom has altered substantially in the last decade as a result of a variety of influences. A shorter and more structured training process known as the Calman reforms was introduced.1 In addition, other factors such as technological innovation, the increased awareness of issues relating to clinical governance,2 and the effect of the European Working Time Directive3 have all affected postgraduate training. In surgical specialties such as ophthalmology, there has been growing concern that these changes were compromising practical aspects of training, particularly with respect to basic specialist training (BST).4, 5 In a previous paper, we reported the initial analysis of a national survey of Senior House Officer (SHO) training, which showed that the majority of SHOs did not receive adequate basic surgical training: only 42% of those who had completed 2 or more years’ training met the Royal College of Ophthalmologists minimum requirement of 50 complete intraocular operations and women were significantly less likely to have done so than men.6 In this paper, we describe the laboratory- and patient-based training that contribute to these short comings and examine in greater detail the influence of socidemographic (gender, ethnicity, and country of medical qualification) and organisational (list size and protected teaching time) factors. We also report the views of SHOs themselves with regard to their basic surgical training.

Methods

Questionnaire

A self-completion questionnaire was developed to describe SHOs’ surgical experience in relation to the recommendations set out by the Royal College of Ophthalmologists in their Guide For Basic Specialist Training.7 The guide provides a formally structured programme involving both laboratory- and patient-based training. Laboratory training entails a requirement (recently made mandatory) to attend a basic laboratory course in microsurgical skills before progressing to intraocular surgery and, throughout the period of training, access to simulated surgical facilities (wet labs) in which to practises surgical skills outside the operating theatre.

Surgical training on patients begins with mastering the various components of the phakoemulsification procedure (‘part phako’) before performing the complete procedure (‘full phako’), all under supervision. The overall expectation is that, by the end of the second year of training, SHOs should have achieved reasonable proficiency in phakoemulsification and performed a minimum of 50 complete intraocular operations under supervision.

The questionnaire asked about laboratory training and facilities, theatre lists, surgical experience, contact with their local College Tutor, and background and demographic details including self-assessed ethnicity, using the Office for National Statistics categories.8 A final section invited any comments the respondent would like to add with regard to surgical training as an SHO. Phakoemulsification was used as the exemplar procedure throughout the questionnaire. To reduce reporting error, respondents were asked to report their activities in the previous week and in the week prior to that; these were then averaged to give rates per week. Longer time frames were used as appropriate.

Respondents

Using the Directory of Training Posts in Ophthalmology, 2000–2001, 476 ophthalmology SHOs were identified. Between November 2000 and October 2001 numbered questionnaires were distributed to named individuals in each post. A total of 10 were subsequently excluded because the questionnaire was returned by the post office or the respondent indicated that the hospital post was not recognised for surgical training (eg it was designed for general practice vocational training only). Individuals who did not respond within 2 months were sent a follow-up questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

Questionnaire responses were entered onto a PC and analysed using SPSS 11.0 for Windows. Statistical tests included χ2 for categorical data, and t-tests, one-way analysis of variance, Pearson's correlation coefficient (r), and multiple regression for interval data.

Qualitative analysis

Free text comments made by respondents in the final section of the questionnaire were analysed thematically.9, 10, 11

Results

Sample

Useable questionnaires were returned by 314/466 SHOs in recognised surgical training posts (a response rate of 67%).

The average age of respondents was 29.9 years (95% CI 29.5–30.3, minimum 24, maximum 46). The mean length of time as an SHO in the UK was 20.1 months (95% CI 18.5–21.6, minimum 1, maximum 103). Other characteristics are given in Table 1. No information is available on the characteristics of nonresponders but comparison between the study sample and all SHOs in ophthalmology in England shows a good match in relation to gender.12 Figures are not available for Wales, Scotland, or Northern Ireland or for other demographic and background characteristics.

Laboratory-based surgical training

Attendance at basic surgical training courses:

In all, 48% of respondents (149/313, 95% CI 42–53%) had attended a basic microsurgical course; 52% (162/314, 95% CI 46–57%) had attended a basic course in phakoemulsification; and 67% (210/314, 95% CI 62–72%) had attended at least one of these courses. The proportion of respondents who had completed at least one course increased with time, with 74% (192/258) of those who had completed more than 6 months training as an SHO having completed a basic surgical course compared with 32% (18/56) of those in their first 6 months of training. Those who qualified overseas were more likely to have attended at least one course (73% vs 62%, χ2=4.23, 1 d.f., P<0.05); there were no differences by gender or ethnic group.

Wet lab experience:

In all, 40% of SHOs (124/310, 95% CI 35–45%) had access to a wet lab; 30% (93/310, 95% CI 25–35%) in their own hospital and 10% (31/310, 95% CI 7–13%) in a nearby hospital. Men were more likely than women to have access to a wet lab (45 vs 30%, χ2=6.23, P=0.013) as were those who qualified in the UK (49 vs 28%, P<0.001); there were no differences between ethnic groups. In all, 39% of respondents (118/299, 95% CI 34–45%) had spent time in a wet lab in the previous six months (mean 8.1 h, SD 9.3, minimum 1, maximum 60). Of those SHOs in their first year of training, 46% (49/107, 95% CI 36–55%) had spent time in a wet lab (mean 8.2 h, SD 8.7, minimum 1, maximum 50 h).

Patient-based surgical training

Theatre opportunities:

In all, 96% of respondents (302/314, 95% CI 94–98%) had been present in their hospital for at least one of the 2 weeks prior to completing the questionnaire, of whom 301 had attended at least one theatre session. Analyses in this section will be confined to these 301 respondents. During this 2-week period, the mean number of operating sessions attended per week was 1.72 (SD 0.7459, minimum 0.5, maximum 8.5) and the mean numbers of patients per list was 4.9 (SD 1.62, minimum 0.5, maximum 12.5).

Cataract surgery performed:

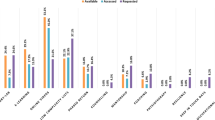

The mean number of part phako procedures performed per week was 0.79 (SD 1.135, minimum 0, maximum 5); this was negatively correlated to the length of time as an SHO (r=−0.232, P<0.01). Women completed significantly more part phakos per week than men (t=2.36, 186.5 d.f., P=0.019, mean difference 0.34, 95% CI 0.06–0.62); there were no differences by ethnic group or where they qualified. Figure 1 shows the mean number of part phakos completed by male and female SHOs by the length of time in training.

The mean number of full phako operations performed per week was 0.74 (SD 1.194, minimum 0, maximum 6); this was positively correlated to the length of time as an SHO (r=0.286, P<0.01). Men completed significantly more full phakos per week than women (t=2.97,291 d.f., P=0.003, mean difference 0.38, 95% CI 0.631–0.128); there were no differences by ethnic group or where they qualified. Figure 2 shows the mean number of full phako procedures completed by male and female SHOs by length of time as an SHO.

Operating list size and surgical training:

Respondents with larger operating lists (ie a larger total of cases per week) performed more full phako operations per week (r=0.237, P<0.001). For those respondents who had at least some protected teaching time in the previous 2 weeks (233/301, 77%), the correlation between the number of cases on their lists and the number of full phakos performed remains (r=0.239, P<0.001) but for those without protected teaching time (68/301, 23%), the relationship disappears (r=0.156, P=0.2).

Multivariate analysis

As the bivariate analysis showed that length of time as an SHO, list size per week and gender were significantly related to mean number of full phakos performed in a week, all three variables were entered into a multiple linear regression to predict mean number of full phakos performed per week. The results suggest that each variable makes an independent additional contribution in explaining the number of full phakos performed per week (Table 2). In other words, those with more cases per week performed more full phakos per week whatever their gender or the length of time they had been an SHO and those of male gender performed more full phako operations whatever the number of cases on their lists per week and their length of time as an SHO.

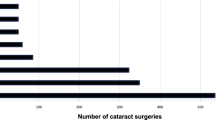

Procedures completed since starting as an SHO

Since starting as an ophthalmic SHO in the UK, 90% (276/305, 95% CI 87–94%) of the respondents had carried out at least one part phako procedure (mean 35.3, SD 36.81, minimum 0, maximum 300); 61% (192/313, 95% CI 56–67%) had performed at least one full phako operation (mean 25.04, SD 40.48, minimum 0, maximum 360); and 34% (108/309) at least one extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE) (mean 3.36, SD 11.31, minimum 0, maximum 141).

In all, 19% of SHOs (60/313) had completed 50 or more full phako operations. Men were significantly more likely to have completed 50 full phakos than women (24.2% vs 10.4%, χ2=8.95, 1 d.f., P=0.003); there were no differences by ethnic group or where they qualified. Figure 3 shows the proportion of male and female SHOs who had completed 50 full phakos by length of time as an SHO.

College Tutor appraisal

In all, 80% (271/307) of respondents had met their College Tutor to discuss their surgical training at least once since they had started as an SHO; 72% (221/307) had done so in the previous 6 months. There were no differences between respondents by gender, ethnicity, or where they qualified.

Comments by SHOs on their experience of surgical training

Respondents were invited to add comments at the end of the questionnaire; 42% (131/314) did so, and 98% (128/131) wrote negative comments. Virtually all their comments were about the shortcomings of basic specialist training.

Three main themes were identified. Examples are included to illustrate each. While comments were coded using the method of constant comparison in order to define and refine the themes, no attempt was made to quantify their exact frequency of occurrence.

The most common theme was the limited opportunities SHOs had for wet lab practice and practical surgery.

Not enough access to wet lab/hands on experience in order to achieve the College's recommendations in 2 years.(Asian female, 12 months as SHO)There is no time for an SHO to operate comfortably with constant heavily booked lists. Often we end up not doing a case due to time pressure.(Asian male, 6 months as SHO)

Where they offered an explanation for their limited experience, respondents did so in terms of two sets of pressures: firstly, the demands of service commitments, which were perceived to limit the time that they could spend on wet lab or practical training and secondly, pressures of clinical governance, which were perceived as militating against ‘hands on’ experience with patients.

Pressure to do as many patients as possible on the list means training is the first to be compromised.(White male, 16 months as SHO)Theatre and pre-assessment during same session. Also get called out of theatre to help in clinic.(White female, 26 months as SHO)Unless mandatory you can’t make consultants train SHOs. Most of the consultants I have worked with are not keen to train due to medico legal constraints.(Asian male, 37 months as SHO) In my unit all operations are automatically entered onto a database. There is continuous audit of complications and monthly league tables. The consultants appear unwilling to let juniors operate in case they will affect their standing in the league table. Complications turn into critical incidents(Asian male, 12 months as SHO)

The second theme was experience of poorly structured training programmes even within recognised SHO training rotations.

There is often no continuity in surgical training as one moves from hospital to hospital or from firm to firm within hospital. This results in duplication, regression and unsteady surgical progress.(Black or other male, 30 months as SHO)Level and quality of training very haphazard and dependent on chance. No correlation with trainees needs, no structure.(Black or other male, 30 months as SHO)

The third theme in the SHO's comments was their sense that consultants were not interested in training them and lacked the skills to do so.

There is a distinct lack of will to teach SHOs among some consultants.(Black or other male, 32 months as SHO) Until you start to re-train consultants, assessing SHO training is pointless. After all, who is training the teachers?(Asian male, 36 months as SHO)

Discussion

This paper reports the first detailed, nation-wide investigation into basic surgical training in ophthalmology in the UK, using cataract surgery as an exemplar procedure. Cataract surgery is the most common intraocular procedure performed by ophthalmologists and so provides the clearest picture of current training experience. Although the data were collected in 2001 the curriculum and structure of BST has remained unchanged and the findings are relevant to current practice. They will also provide a baseline against which future training can be measured. In our previous paper, we reported that the majority of SHOs performed limited surgical activity and only a minority had met the standard expected by the College after 2 years of training.6 In this paper, we have examined in greater detail the laboratory and weekly theatre experience leading to the shortfall in training and additionally have investigated the differences in training received according to gender, ethnicity, and place of qualification of the SHO. The strengths of the study derive from the research design, which involved contacting individuals in all recognised training posts in ophthalmic surgery throughout the UK and collecting detailed information on their surgical activity over specified time periods and from the high response rate. The main limitation is the reliance on self-reported data that cannot be verified independently. A focus on the previous week and the week prior to that, however, helps to increase confidence in the accuracy of the data as does the internal consistency in the findings.

The role of surgical skills laboratories (or wet labs) in surgical training is controversial: some believe them to be an effective teaching method,13, 14 while others have questioned their role, and their ability to replicate the reality of surgical experience.15 Nevertheless, learning basic surgical techniques outside the operating room has clear advantages over learning on patients. This survey has shown that, while most SHOs attend a microsurgical course early in their training, wet lab training is rarely incorporated into training schemes and only used sparingly by trainees. The debate on surgical training in the UK, much of it in relation to the proposed reduction in the length of training and the European Working Time Directive,3 has identified skills courses and wet labs as important in the training of future surgical consultants in the face of reduced operating time. The findings of this study suggest that considerably more thought needs to be given to how these facilities can be developed if they are to play an effective role in surgical training in ophthalmology.

With regard to patient-based training, we found that the number of full phakos SHOs performed per week increased with their length of time as SHO while the number of part phakos decreased, a finding which suggests that SHOs are moving appropriately from part phakos to full phakos as they gain more experience. Perhaps less expected is the finding that the number of full phakos performed also increased with the number of theatre cases per week, so long as some time was protected for teaching time. This suggests that large numbers of cases per se are not a limiting factor in allowing SHOs the opportunity to perform full phakos but that the organisation within hospitals (in providing protected time) is. Indeed, where organisation is good, large numbers of cases are a positive resource in training SHOs. By contrast, independent sector diagnostic and treatment centres driven by a different agenda are unlikely to provide a useful training resource for the trainees.

Changes in the external working environment of surgery in general and ophthalmology in particular has demonstrable effects on surgical training.5, 16, 17 However, there is limited information available on how sociodemographic differences affect training. In this study, we found no differences on any measure with regard to ethnicity, a finding consistent with the observation that there is no ‘ethnic penalty’ for professionals in employment in the UK.18 Similarly, few differences were found by place of qualification: overseas doctors were less likely to have access to wet lab facilities but more likely to have completed a basic surgical training course. In striking contrast to these findings, however, were those with regard to gender. Female SHOs were disadvantaged with regard to both laboratory- and patient-based training. Women performed more part phako procedures per week than men but fewer full phakos and this was so when both the length of time they had spent as an SHO and the number of cases on their lists per week were controlled for. As a consequence, women are significantly less likely than men to have performed the expected 50 full phakos after completing 2 years of training as an SHO, as we reported in our previous paper.6 It is not obvious why this appears to be the case as the jobs are gender independent. However, similar findings have been reported in other studies.19, 20 Studies of junior hospital doctors in other specialties have pointed to bullying as a potential contributing factor.21

The role of the College Tutor in influencing surgical training needs to be reconsidered; although almost three-quarters had met with their tutor in the previous 6 months, less than half the trainees had fulfilled the surgical component of the curriculum after 30 months as an SHO.

The free text comments made by the SHOs at the end of the questionnaire offer an insight into the nature of their frustrations regarding surgical training. Almost half the respondents added comments, almost all of which were negative, a pattern similar to that found in other studies of junior doctors.10 Despite the guidelines of the College, these doctors felt there was a lack of structure to surgical training, with limited access to basic courses and wet lab facilities. Practical surgical experience was seen as variable and disjointed between individual firms and when rotating between hospitals. In addition, the fear of complications and the pressure of the service commitments were perceived to reduce surgical opportunities. As those who provided comments were self-selected and potentially unrepresentative, care should be taken in making generalisations on the basis of these comments. However, when taken in conjunction with the quantitative data on their laboratory training and surgical experience, they suggest not only that the surgical training SHOs receive is inadequate but also that the trainees recognise this and are frustrated and dissatisfied with it. The explanations they offer may provide a starting point for more careful investigation of the factors that undermine their training experience and influence providers of training.

Concern over the surgical component of BST is not confined to ophthalmology or even surgical specialties. Other specialities are also struggling to determine the best configuration for BST.22, 23, 24, 25, 26 The study described here shows that ophthalmology faces formidable and specific challenges for training to ensure that appropriate candidates are available for the future consultant workforce. The findings of this study suggest that unless continued efforts are made to improve surgical training, more trainees will struggle to gain the necessary surgical skills in the required timeframe. With the impending constraints of the European Working Time Directive, increased political influence on surgical activity,27 and the major reforms in the SHO grade proposed by the Department of Health,28 basic surgical training may become even more of an issue in ophthalmology than other surgical specialties.

Ethical approval: Oxford Brookes University; St Mary's LREC advised no NHS ethics approval required.

References

Calman KC . Hospital doctors: training for the future. The report of the working group on specialist medical training. HMSO: London, 1993.

NHS Executive. Clinical governance: Quality in the new National Health Service. 1999.

Department of Health. European Working Time Directive (EWTD). Delivering effective medical training under EWTD. (www.dh.gov.uk/PolicyAndGuidance/HumanResourcesAndTraining/WorkingDifferently/EuropeanWorkingTimeDirective/fs/en (accessed 8 June 2004.

Fielder AR, Watson MP, Seward HC, Murray PI . Action on cataracts should influence surgical training. BMJ 2000; 321: 629.

Gibson A, Boulton M, Watson M, Fielder A . Surgical training in ophthalmology. Lancet 2002; 360: 1702.

Watson MP, Boulton MG, Gibson AR, Murray PI, Moseley MJ, Fielder AR . The state of basic surgical training in the UK, ophthalmology as a case example. J R Soc Med 2004; 97: 174–178.

Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Guide for Basic Specialist Training 2000 (www.rcophth.ac.uk/edu-train/edu-train-docs/guidetoBST.pdf) (recently updated).

Office for National Statistics. The Classification of Ethnic Groups. London Office for National Statistics, 2001 (www.statistics.gov.uk/Calssification/ns-ethnic-classification.asp) accessed 26 January 2004.

Fitzpatrick R, Boulton M . Qualitative methods for assessing health care. Qual Health Care 1994; 3: 107–113.

Garcia J, Evans J, Redshaw M . Is there anything else you would like to tell us? Methodological issues in the use of free-text comments from postal surveys. Qual Quant (in press).

Pope C, Ziebland, S, Mays N . Analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000; 320: 114–116.

Department of Health. Medical and Dental Workforce Census. Department of Health: London, 2002 (www.doh.gov.uk/stats/mdworkforce_03.pdf).

Qayumi AK, Cheifetz RE, Forward AD, Baird RM, Litherland HK, Koetting SE . Teaching and evaluation of basic surgical techniques: the University of British Columbia experience. J Invest Surg 1999; 12: 341–350.

Velmahos GC, Toutouzas KG, Sillin LF, Chan L, Clark RE, Theodorou D et al. Cognitive task analysis for teaching technical skills in an inanimate surgical skills laboratory. Am J Surg 2004; 187: 114–119.

Spitz L, Kiely EM, Piero A, Drake DP, McAndrew F . Decline in surgical training. Lancet 2002; 359: 83.

Morris-Stiff G, Ball E, Torkington J, Foster ME, Lewis M, Harvard T . Registrar operating experience over a 15-year period: more, less or more or less the same? Surg J R Coll Surg Edinburg Irel 2004; 2: 161–164.

NHS Executive. Action on Cataracts: Good Practice Guidance. NHS Executive: London, 2000.

Heath A, McMahon D, Roberts J . Ethnic differences in the labour market: a comparison of the samples of anonymized records and Labour Force Survey. J R Stat Soc: Ser A Stat Soc 2000; 163: 303–339.

Cooke L, Hurlock S . Education and training in the senior house officer grade: results from a cohort study of United Kingdom medical graduates. Med Educ 1999; 33: 418–423.

Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ, Evans J . Views of junior doctors about their work: survey of qualifiers of 1993 and 1996 from United Kingdom medical schools. Med Educ 2000; 34: 348–354.

Quine L . Workplace bullying in junior doctors: questionnaire survey. BMJ 2002; 324: 878–879.

Chikwe J, de Souza AC, Pepper JR . No time to train the surgeons. BMJ 2004; 328: 418–419.

Darke S . Training in operative vascular surgery: gaining experiences and competence. Ann R Coll Surg Engl (Suppl) 2001; 83: 258–260.

Crofts T, Griffiths J, Sharma S, Wygrala J, Aitken R . Surgical training: an objective assessment of recent changes for a single health board. BMJ 1997; 314: 891–895.

Postgraduate medical education and training the medical education standards board: a paper for consultation. Royal College of Physicians, London, March 2002.

Carty E, Neville E, Pembroke M, Wade A . A curriculum for SHO training—what is it and why has it changed? Clin Med 2001; 1: 50–53.

Department of Health. Growing capacity—diagnostic and treatment centers, 2003 (www.doh.gov.uk/growingcapacity/news.htm) accessed 27 October 2003.

Department of Health. Modernising Medical Careers, 2004 (www.mmc.nhs.uk) accessed 25 May 2003.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Alcon Laboratories for a Grant of £7000 to cover the costs of conducting the study and for help with distributing questionnaires. Alcon Laboratories have had no part in the design, conduct, or analysis of the survey or the presentation of findings. Miss HC Seward provided helpful comments and support during the project. Preliminary data from the study were presented as a poster at the 2002 Annual Congress of the Royal College of Ophthalmologists.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gibson, A., Boulton, M., Watson, M. et al. The first cut is the deepest: basic surgical training in ophthalmology. Eye 19, 1264–1270 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6701754

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6701754

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The impact of distance cataract surgical wet laboratory training on cataract surgical competency of ophthalmology residents

BMC Medical Education (2021)

-

Perceptions of training in gonioscopy

Eye (2019)

-

Evaluation of the learning curve of non-penetrating glaucoma surgery

International Ophthalmology (2018)

-

Gender differences in the acquisition of surgical skills: a systematic review

Surgical Endoscopy (2015)

-

25th RCOphth Congress, President's Session paper: 25 years of progress in surgical training

Eye (2014)